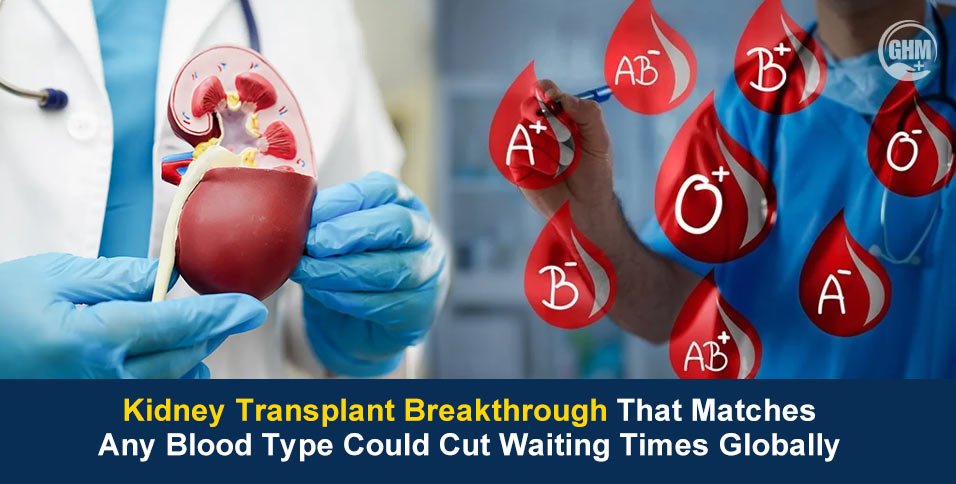

In a major kidney transplant breakthrough, scientists have created a “universal” kidney that can match any blood type. It is a development that could transform organ transplant systems worldwide.

By removing blood group antigens (the markers that make blood types different), researchers have taken a critical step toward eliminating one of the biggest barriers in organ transplantation: blood type compatibility.

This innovation, recently reported by an international team of transplant researchers, used enzyme technology to strip A blood group antigens from a donor kidney. When tested in a brain-dead patient maintained on life support, the organ temporarily behaved like an O-type kidney, the universal donor blood type.

While more clinical research and trials are needed before universal organs are ready for real-world use, the implications for transplant waitlists, patient survival, and healthcare equity are enormous.

Why Blood Type Matters in Organ Transplants

Every person has a blood type, A, B, AB, or O, determined by specific antigens on the surface of their red blood cells and tissues. These blood group antigens act like “ID tags.”

- If a recipient receives an organ with incompatible antigens, their immune system sees it as foreign and attacks it, leading to rejection.

- O-type organs are the most in demand because they can be transplanted into any blood type, making type O donors especially valuable.

- Patients with rarer blood types, like B or AB, often face longer waiting times.

According to the World Health Organisation, over 100,000 people globally are on kidney transplant waiting lists at any given time, with thousands dying each year before receiving a suitable organ.

The Science Behind the Breakthrough

At the heart of this innovation is the removal of A antigens from donor kidneys. Researchers applied specially engineered enzymes to the kidney’s surface. These enzymes act like microscopic scissors, carefully cutting away the antigens that mark it as “A type.”

Once the antigens were removed, the kidney temporarily resembled an O-type organ. In the early proof-of-concept trial:

- The converted kidney was transplanted into a brain-dead patient on life support.

- The immune response was monitored, showing no immediate attack from the recipient’s blood.

- However, some A antigens reappeared by day three, which signals that more work is needed before long-term use in living patients.

Despite this limitation, experts consider it a historic moment. It demonstrates that blood type conversion of solid organs is technically possible.

Impact on Kidney Transplant Waitlists & Mortality

The potential impact of universal kidneys on waitlists is striking. Currently:

- Blood type O recipients wait longer for organs because their compatible pool is smaller.

- Many patients die before a match is found or rely on lifelong dialysis, which is expensive and lowers quality of life.

- Universal organs could remove blood type from the allocation equation, meaning more flexible and faster matches.

A modelling study from several transplant centres suggests that if just 30% of kidneys were made universal, wait times could drop by 20–40%, and hundreds of lives could be saved annually.

This could also:

- Reduce geographical and blood type disparities in transplant access.

- Shorten the cold ischemia time (the period organs spend outside the body before transplantation).

- Improve overall system efficiency and patient outcomes.

The Immune System: Tolerance vs. Rejection

Even with antigen removal, the immune system remains a powerful gatekeeper. Transplant tolerance, the state in which the body accepts a new organ without attacking it, is not guaranteed.

When antigens are stripped:

- The immune system may still detect other minor histocompatibility markers, triggering rejection.

- Immunosuppressive drugs are still likely to be needed, though possibly in lower doses.

- There’s a risk that antigens may reappear over time, as seen in the early trials.

Future research may explore immune retraining, ways to teach the body to accept organs more naturally, through cellular therapies, gene editing, or personalised immunomodulation.

Future Possibilities in Transplant

While kidneys are the first focus, the same enzyme technology could potentially be applied to other solid organs, including hearts and lungs. That would require overcoming:

- More complex vascular and tissue structures.

- Stronger immune reactions in other organ types.

- Regulatory and ethical considerations for first-in-human trials.

If successful, this approach could lead to a universal donor organ bank, radically changing global transplantation.

Conclusion

The path from lab bench to bedside involves phased clinical trials, regulatory approvals, and long-term immune monitoring. But transplant specialists are optimistic.

For now, this kidney transplant breakthrough offers hope that in the near future, a patient’s blood type won’t determine their chance of survival.